Have you ever wondered how electrical appliances in our homes and workplaces maintain safe operation? One pivotal safety mechanism is electrical grounding. In technical terms, grounding establishes a backup pathway for electrical current to dissipate into the earth in the event of wiring faults. Essentially, it creates a direct electrical connection between the earth and the electrical equipment within your property.

Electrical outlets and appliances pose inherent risks when malfunctions occur. Without proper grounding, a fault could redirect electrical current through human bodies, resulting in electric shock or severe injury. Electrical grounding mitigates this hazard by acting as a safety buffer: it provides a low-resistance pathway for unintended current to flow away from people and equipment, safely dissipating into the earth.

Grounding is a fundamental component of electrical system safety, designed to channel excess current into the earth via a low-resistance path. Unlike hot wires (which carry active current) and neutral wires (which return current to the source), the grounding wire serves as a dedicated backup route.

When a fault occurs—such as a loose wire, damaged insulation, or component failure—current may leak from the circuit. This leakage can energize the metal casings of appliances, creating a shock hazard for anyone who touches them. Grounding prevents this by offering a far more accessible path for the stray current: through the grounding wire, down to a grounding electrode (a metal rod or plate buried deep in the earth).

The earth functions as an infinite electrical sink, capable of safely absorbing large volumes of current. Grounding wires—typically constructed from bare copper for optimal conductivity—connect the appliance chassis to the grounding electrode. At the main electrical panel, the neutral wire is also bonded to the grounding system. This bond stabilizes voltage levels within the circuit, ensuring reliable performance of electrical devices.

In summary, electrical grounding is indispensable for preventing electric shock and electrical fires, serving as a cornerstone of any safe electrical system.

Electrical appliances are vulnerable to power surges—sudden voltage spikes caused by storms, utility grid fluctuations, or equipment malfunctions. A grounded system provides a safe discharge path for excess voltage, diverting it into the earth and protecting sensitive electronics from irreversible damage.

Grounding facilitates the uniform distribution of electrical power throughout the system, preventing circuit overloading (which can trigger breaker trips or equipment failure). The earth acts as a universal reference point for voltage sources, ensuring consistent voltage output across the entire electrical network.

The earth is a natural conductor, capable of carrying excess current with minimal resistance. By grounding electrical systems, we prioritize this low-resistance path for stray current, diverting it away from human bodies and equipment.

Faults such as loose wires or failing components can generate leakage current. Without grounding, this current may seek alternative paths through flammable materials (e.g., insulation, wood), generating heat and igniting fires. Grounding provides a dedicated, low-resistance pathway for leakage current, directing it safely into the earth and eliminating the fire risk.

An ungrounded system exposes both equipment and people to heightened risks. High-voltage surges can destroy appliances beyond repair; in extreme cases, they can spark fires that threaten property and lives. Grounding acts as a critical barrier against these hazards.

A fully functional grounding system relies on several interconnected components, each serving a specific role:

A conductive device that establishes direct contact with the earth. Common examples include metal rods driven into the ground, buried metal plates, or buried metal water pipes (though regulatory restrictions may limit the use of water pipes). Its purpose is to create a stable electrical connection to the earth, serving as a reference point and safely absorbing fault current.

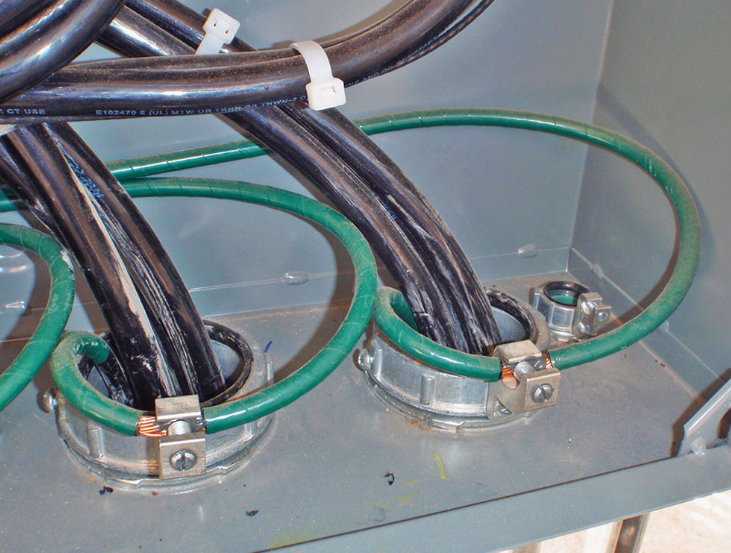

A wire that connects the grounding electrode to the rest of the grounding system. Typically made of copper or aluminum, it must be sized appropriately to safely carry the maximum potential fault current from the electrical system to the grounding electrode.

A metal bar within the electrical panel that serves as a central hub for all grounding wires. It is bonded to the grounding electrode conductor, ensuring a continuous, reliable path for current to flow into the earth.

Specialized clamps or terminals that securely connect metallic components (e.g., appliance casings, pipes, conduit) to the grounding system. They create a unified conductive network, allowing stray current to flow freely through all connected parts and safely dissipate into the grounding electrode.

By maintaining a continuous current path, bonding connectors prevent unintended voltage buildup on metallic surfaces, minimizing shock risks and reducing the potential for fires caused by arcing or overheating at connection points.

While electrical work should always be performed by licensed professionals, homeowners can conduct a basic preliminary check (with power disconnected) to assess grounding integrity:

Affordable and simple to use, these tools verify proper wiring in 2-prong and 3-prong outlets. The tester illuminates when probes contact the hot and neutral slots of a correctly wired outlet. For grounding checks, touching the neutral probe to the ground screw (on the outlet faceplate or third prong) should also trigger illumination—if not, the outlet is improperly grounded.

User-friendly devices that plug directly into 3-prong outlets. They use LED light patterns to indicate common issues, including proper wiring, reversed polarity, open circuits, and missing grounding.

Widely used by electricians, multimeters can also be employed by homeowners to check for grounding faults. The testing process is similar to that of neon circuit testers but offers more precise readings.

While electrical grounding is critical for overall safety, prioritizing personal safety during any electrical work is paramount. Grounding systems are complex—attempting DIY repairs can exacerbate issues or create new hazards. Always:

In electrical systems, “grounded” refers to a direct electrical connection to the earth. It acts as a safety net, similar to a lightning rod—providing a harmless path for stray current to dissipate into the earth instead of causing shock or fire.

An open-ground outlet is a 3-prong outlet with a non-functional grounding system. It has a slot for a grounded plug but lacks a connected grounding wire. This is dangerous because stray current has no safe path to escape, increasing the risk of shock or fire if a fault occurs. Always have open-ground outlets repaired by a licensed electrician.

Electrical tape may provide temporary insulation for a ground wire in an emergency, but it is not a long-term solution. Tape deteriorates over time, loosens, and peels—exposing the wire and creating hazards. For safe, permanent connections, use approved methods such as wire nuts or crimp connectors.

Grounding is an unsung hero of electrical safety, quietly protecting homes, workplaces, and lives by diverting dangerous current away from people and equipment. By understanding its role and prioritizing professional maintenance, you can ensure a safe, code-compliant electrical system for years to come.